In 1942, Albert Camus wrote one of the punchiest one-liners of the twentieth century — which itself captured one of the most enduring philosophical challenges in all of human history:

“To decide whether life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question of philosophy.”

“Everything else,” he wrote, “is child’s play; we must first of all answer the question.”

But then, as chance would unfortunately have it, many were robbed of the opportunity to answer this question for themselves. Because it was in 1942, that same year Camus called attention to the question, that more than a million humans were captured and taken to Auschwitz.

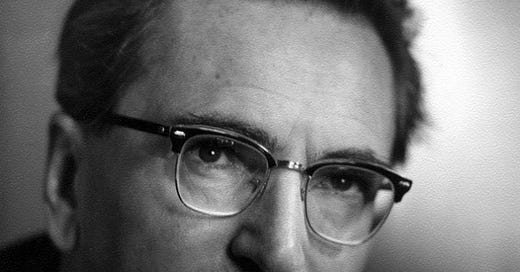

And among these millions who were deemed unworthy to live, was the young Viennese psychiatrist, Viktor Frankl.

He and his family would be taken to the Theresienstadt concentration camp before moving to Auschwitz. And after 3 long grueling years— witnessing his father’s death by exhaustion and discovering later the murder of his mother, wife and brother— Viktor would settle down in Vienna and return to the heart of Camus’ philosophical dilemma.

Because as you could imagine, at that time for Frankl, the issue was more relevant than ever: the question of whether life is worth living or not.

Sometimes, life asks this question not as a thought experiment but as a gauntlet hurled with the raw brutality of living.

His response eventually came in 1946. It was after he compiled and edited a set of his own lectures on moving beyond optimism and pessimism to find the deepest source of meaning. The result was a slender book published in Germany.

However, at the time, for whatever reason, the book was overlooked and went out of print shortly after.

And in fact, despite Frankl’s renown in the U.S., it was only recently that an english translation came into print under the apt title, Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything

In it, he emphasizes that the impact one has on reality (outwardly and inwardly) is driven by creative action.

“Everything depends on the individual human being, regardless of how small a number of like-minded people there is, and everything depends on each person, through action and not mere words, creatively making the meaning of life a reality in his or her own being.”

To further clarify, the expression of meaning that drives creative action is what Frankl believed to be the primary motivating force in a person’s life.

(And it was this conviction in fact that served as his theoretical orientation for his therapeutic practice called, logotherapy.)

Moreover, to him, asking about what the meaning of life is, is itself an improper question. Instead, you need to invert it…

At this point it would be helpful [to make] a conceptual turn through 180 degrees, after which the question can no longer be “What can I expect from life?” but can now only be “What does life expect of me?” What task in life is waiting for me?

Through this inversion of the question, it is now life that is asking you the question, “What will you do with the life you were given?”

This is a clever angle. Because now, as a consequence of life asking us this question, an important dynamic emerges.

The onus is on us.

Elsewhere in the same book, he elaborates that it’s our responsibility to affirm life through our responding to its question:

Living itself means nothing other than being questioned; our whole act of being is nothing more than responding to — of being responsible toward — life.

In other words, on a fundamental level, the greatest source of meaning in life comes from taking on as your primary responsibility, the affirmation of life.

He also gets at a crucial point that there is no cookie-cutter answer in responding to life’s question. Meaning that each answer must be, by nature, a unique response — given that we are all unique individuals with our own unique desires.

Frankl writes:

The question life asks us, and in answering which we can realize the meaning of the present moment, does not only change from hour to hour but also changes from person to person: the question is entirely different in each moment for every individual.

We can, therefore, see how the question as to the meaning of life is posed too simply, unless it is posed with complete specificity, in the concreteness of the here and now. To ask about “the meaning of life” in this way seems just as naive to us as the question of a reporter interviewing a world chess champion and asking, “And now, Master, please tell me: which chess move do you think is the best?” Is there a move, a particular move, that could be good, or even the best, beyond a very specific, concrete game situation, a specific configuration of the pieces?

In this way, Frankl here doesn’t just mean our question to life must be unique from others. This also applies to our many selves throughout our lives!

Meaning there’s no use cheating the question by copying our response we gave to life a day, hour, or even a minute ago. As each moment arrives fresh with new potential.

So in conclusion, take courage and say yes to life in your own creative way — bearing it as your own responsibility to do so. Because, according to Frankl, only then do you find the deepest source of meaning.