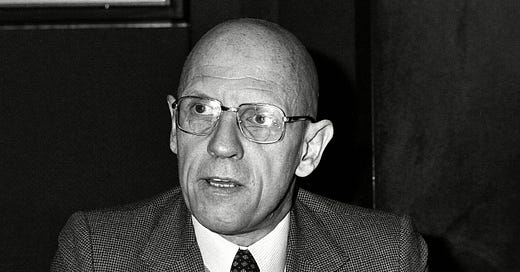

According to a recent analysis, Michel Foucault has 1.42 million citations on Google Scholar, which is roughly 75% more than any other author in history. This ultimately means that, to this day, only The Bible has a greater impact than Foucault on shaping Western society and culture. Or, if we’re just to look at this on an individual level, it can justifiably be said that Michel Foucault is the most influential person in the history of modern civilization.

But why is this?

Well, let’s just say it’s not due to him being an easy read. His ideas can often be overly abstract and somewhat dense. And more than that, he wasn’t the most prolific writer. For example, Noam Chomsky, who’s basically a deity in the field of linguistics, has written or contributed to over 1,100 published works, while Foucault’s contributions amount to a little more than 400. And when you do the math, this is virtually less than half of Chompsky’s total. But the irony in this is that Chompsky’s citation count (514,316) is virtually less than half of Foucault’s.

So again, what makes Foucault so exceptional that he outpaces every other thinker in citations?

The answer to this lies in how his ideas have struck at the core of contemporary political science and philosophy.

Particularly those ideas regarding the pervasiveness of power up and down and through institutions of every kind, as well as his critiques of modern structures like prisons, asylums, and schools.

To help us get a better grasp of the magnitude of this idea’s impact, let’s draw our attention to the scientist, Eric Lander, who was associated with the Human Genome Project (remember that multi-billion-dollar international project back in the early 2000s?), which, with the help of his colleagues, successfully sequenced the majority of the genome. It was a pretty big deal, to say the least—considering that it was a discovery that instigated thousands of new hypotheses in the field of genomics. This is also something that we can see reflected in the recent analysis, where Eric Lander was referenced 725,654 times.

But now, when you compare this discovery to Foucault’s notion of power, the difference is taking the impact of the genome project (quantified in the number of works cited) and essentially more than doubling it.

Now, to get more into the specifics of what made Foucault’s idea on power so revolutionary, it’s important to first understand that Foucault shattered the notion that power is merely something held by governments or the elite; instead, he argued that it operates subtly through everyday norms, language, and social practices.

Furthermore, in giving us the linguistic framework to become more aware of institutional overreach, systemic inequality, and how deeply these are woven into the fabric of our lives, he provided for us something that no other person in history had: a vocabulary for resistance. And perhaps more crucially, a vocabulary for understanding our entrapment within systems that shape our very selves.

Last but not least, what made Foucault’s work so attractive and perennial was his refusal to provide answers.

Go ahead and look for yourself—from ideas on sex to institutional power to the architecture of knowledge—Foucault doesn’t tell us what we should do in light of our entanglement in these vast networks of social interaction; he’s like Dorthy from The Wizard of Oz in simply revealing the machinery behind the curtain (or maybe that was Toto?).

This method of critique makes sense when you consider that this is what it meant to Foucault to be a postmodernist: It meant doing the work of Deconstruction.

Deconstruction in philosophy is the business of taking ideas or concepts and putting them through a shredder, as it were. Meaning that you’re pointing out all the flaws and inconsistencies of an idea and after that’s done, you just leave them on the floor.

It’s basically philosophical littering.

And naturally, what follows in the act of pure deconstruction is that there’s a mess left for someone to clean up; to then do the restorative work. All the constructiveness.

And as shitty as that might be of Foucault, the upshot of this approach was that it offered the intellectual equivalent of an open-ended question—and this right here, this ambiguity, this openness—is what might be the most impactful feature that contributed to his unprecedented impact. Foucault essentially asked a million-dollar question without giving a response, which left the door wide open for everyone who would follow.

And follow they did.

It also can’t be ignored that Foucault’s philosophy is so interdisciplinary in nature, and that, too, widens the door of entry even more to inspired researchers. In fields like sociology, anthropology, history, political science, philosophy, etc.

In brief summary, the perfect storm here for making Foucault’s work so popular was its broad applicability paired with a rising sense of political relevance; paired also with the power of Foucault’s critique that prompted later scholars to provide an answer to his deconstruction; paired also with his unwillingness to answer his own question. Hence, the mind-blowing 1.42 million citations.

And there you have it. Our most successful intellectual in the world. The GOAT of academia, Michel Foucault.

I'm a lit student and I was recently introduced to foucault's "Discipline and Punish," especially his concept (which he derived from Bentham) of panopticism and docile body. it blew me away! reading this was freshening!

I'm an English professor and also love studying critical theory, and Foucault has been a mainstay in my work. Great read!