Why You Feel Like a Failure

How to defeat status anxiety

In our modern society, comparing ourselves to others seems as natural as breathing. And technology has only supercharged that instinct.

Smartphones and social media have given us unlimited access to what would otherwise be privately or locally shared — so that the highlights and accomplishments of our friends and family are available to us with just the smallest maneuvers of our thumbs.

But not only just those closest to us, instead this privilege extends to anyone who uses the same technology you do. And let’s be real, that’s basically everyone on planet earth that belongs to a higher civilization. That’s over 3 billion people at your fingertips.

However, even though we may follow, say, 1,000 people, our human nature makes us much more selective for who we compare ourselves with. So that out of that 1,000, it’s more like 10 or so whom we count as critical reference points.

And these reference point are typically not the Brad Pitts and Blake Livelys of the world. For the average human, these super stars are beyond the target of our comparison group; which is why we can track their accomplishments and be genuinely happy for them. But it’s those on the other hand who we count as our peers — our equals — who have our most anxious and special attention.

In other words, it’s our family members, our friends and our co-workers who we have the most difficult time being sincerely happy for.

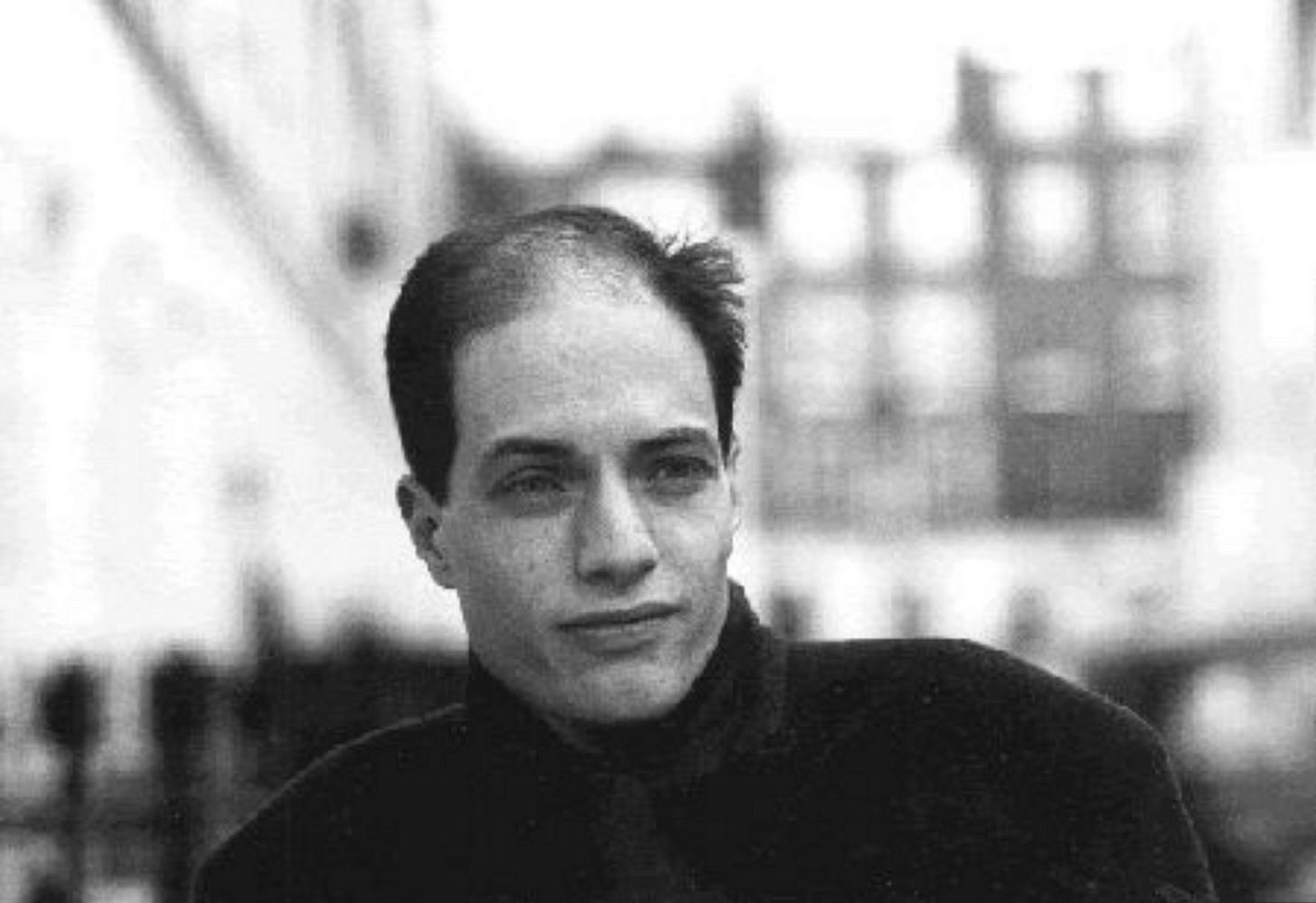

The philosopher, Alan de Button gets at this point further in writing that, “There are few successes more unendurable than those of our ostensible equals.”

The whole thing is a psychological mess, but the main reason why we struggle with the praise of our equals (those who we even call best friends), goes back to a conceptual shift around the late 1700s — when the belief that each person should be given equal opportunity for success, and that each person is endowed with these unalienable rights: of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

And yes, I’m not kidding, you can literally blame the American Dream for your status anxiety.

Let me explain. You see, back in the midieval era, there were a few main stories that people told themselves; and these stories shaped culture and society.

One of the most influential stories was this: that the poor aren’t responsible for their poverty.

Throughout the western world, the wide acceptance of this idea came from a universal understanding of the Christian narrative. It’s that God is in control of your destiny. That what he has willed for your life you cannot escape.

Besides, why would you even want to? Such ambition would indeed only reflect a sinful presumption — that you perhaps know better than an all-good, all-knowing, all-powerful Creator of the universe.

And so within the 3 class structure of that day — between the clergy, nobility and peasantry — there was a mutual respect and appreciation for one another as a consequence. As it was well-understood that each was predetermined, by a loving God, to carry on in the manner of life they were born into.

Add to this also the biblical notion that the poor were good. As in, they were in some real sense, spiritually better than the rich. And what’s more is that the rich weren’t seen as merely neutral in a spiritual regard, but in fact weaker. Which was an idea biblically supported by verses like Matthew 19:23: “It is hard for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of heaven.”

Consequently, such stories had a compounding effect on how the upper classes perceived the peasantry. Poets and artist would even attribute their works to the poor — being that they were the most worthy of dignity and honor.

In a poem written by Hans Rosenplüt of Nuremberg, he exalts the virtue of the poor:

“It is often hard labor for him when

he wields the plough

With which he feeds all the world:

lords, townsmen and artisans.

But if there were no peasant, our

lives would be in a very sad condition”

So as a consequence of this respect from artists and elites, it made being poor somewhat more endurable.

But then everything changes at the dawn of the enlightenment and the industrial revolution. Instead of a biblically informed monarchy, there are governmental system shifts to support a kind of meritocracy. And it’s actually here that the cultural script gets completely flipped — where the rich are seen as morally good and the poor as morally bad.

And so how could such an extreme like this happen?

Story, of course. But more specifically, it was the story that status now has a moral significance.

Which doesn’t sound like that big of a deal, but just go back to Jesus’ time (cerca 30 C.E.) and remember that your essence and quality as an individual (or your moral condition) wasn’t at all determined by status. This is why Jesus could be a carpenter and at the same time be heralded as a moral master; whereas Pontius Pilate, a wealthy imperial officer, could be deemed a terrible sinner.

Thus, in principle, your position didn’t measure into your intrinsic value as a human. Which was also why for the centuries that followed, intelligence and self-awareness could be found lurking in any market place or social arrangement — in a blacksmith or king, a general or housewife.

And mind you, this was also a mainstay alongside the hereditary principle (the idea that royal families are genetically superior or have divine right to rule generation after generation). That is, until Napoleon Bonaparte and others started to speak openly about their despise for this apparently foolish bloodline tradition — as if that were the only qualification for who to recruit as his generals or political leaders. The irony was that the fact of who one’s father was mattered the least in such a selection process. Which was ultimately why Bonaparte abandoned feudal privilege and hired based on competence. A system of carrières ouvertent aux talents (“careers open to talent”).

No wonder he did so well building a global empire…

But like I was saying, it was around the 1800s that status started to be an indicator for one’s moral standing. The evolution of stories was something like this: status and identity was conferred upon birth; it didn’t matter what one did in their lifetime, but who one was; which then gave way to an ambition for removing inherited privilege so that status could be dependent on individual success — which singularly meant financial success; thus, given that the playing field was equal in opportunity, it was implicitly understood that whoever didn’t gain material wealth was defective; it meant that their character was flawed — whether by laziness, impatience, lack of discipline or ambition — the ultimate story was that their achieving of less amounted to them being less.

And so with this massive pressure to avoid being seen as being less, new ways to reach the top of the social hierarchy began to change. The rules of civility were in favor of the self-made man — and so ushered in what we know as the American Dream. A phenomena that, in its most optimistic form, composes the much coveted rags to riches story — a non-fiction account for when a person makes it, shall we say, ‘out the hood’.

One of the many poster boys for this genre is a man by the name of Anthony Robbins, a once obese janitor who became a multi-millionaire.

In his general sales pitch, he basically reiterates and emphasizes the story that created the American Dream. He tells his listeners that they can be like him if they put their minds to it, that “if you truly decide to, you can do almost anything.”

Naturally, what this message does is reinforce our belief that initially gave oxygen to the American Dream. It’s that to be successful and attain status, we must achieve a great deal of financial wealth; and conversely, to have all the opportunity and resources available in the world and not do so, that would mean we simply lack the discipline, patience or ambition to do so — it would mean that we’re less than in our quality as people, lacking “what it takes” at best and morally inferior at worst — or maybe worse still, we’re perceived as belonging to that dreadful category of Losers.

And here’s where it all happens; this is where status anxiety gets unlocked. Because it doesn’t matter what game you’re playing, or where or with whom you’re playing it — being a Loser is much less desirable than not being a Winner. 2nd and 3rd place, for example, are quite cushy in relative comparison to being in the ranks of losers.

Furthermore, this anxiety we all experience in our ambition toward success — it’s a subtle indication that Mr. Robbins words aren’t quite right, that they aren’t reflective of the real world. Because deep down you feel that ‘truly deciding’ to do almost anything you want (which in this context invariably involves achieving financial success) really isn’t that easy as he makes it sound. In fact, when you get down to it, it’s really fucking hard. Yes, I’m sure this doesn’t come as a shock: it’s really-really hard to become successful. (Given that success is a financial goal arbitrated by lofty ambition).

This kind of success is hard because it’s got to do with the same thing as what gives us the anxiety to feel that it’s hard. And that same thing is uncertainty — as both being a true measure of the future and the essence of status anxiety.

One more time in plain english: Uncertainty is the essence of status anxiety.

Practically speaking, this anxiety is in not being safely assured that we have all the talent and know-how to reach a certain goal, or that we won’t be thwarted by some unforeseen market shift, or that our job promotion won’t be threatened by some new hot-shot colleague — all potential failures that could be compounded by the possible success of our peers. Our family and friends.

This is why Alain de Button wrote that “Anxiety is the handmaiden of contemporary ambition.”

Because ask yourself — how can I be so sure that I’ll attain or keep my desired place in the social hierarchy?

Certainly not by beauty. I mean sure, it’s a potent ingredient that elevates some youths to Instagram stardom. But for how long? That’s my point: There’s no peace of mind in having beauty as a value for status since it grows rapidly out of our control.

Luck is another factor that can work in securing status, but it’s appearance is even more uncertain than beauty. Just think of how often you see lottery winners strike it big twice? I’d venture to say never. But even if they do, the statistics show us that the odds of them sustaining that fortune aren’t in their favor. Chances are they’re back to square one (e.g., their favorite slot machine) with the hope that they’ll find Lady Luck’s favor for a third time.

Surely talent then, you might think. That’s a factor we can rely on to be consistent, right? Perhaps not. Alain de Button makes a compelling case that even talent is a fickle thing:

“[Talent] can make an appearance for a time and then unapologetically vanish, leaving our career in pieces.”

Ok, well what about my employer or the stock market? I think the answer is obvious to most. But if you think these are safe bets that ensure your livelihood and esteem, you need not look any further than what took place as a result of the 2008 recession.

There’s No Going Back

The sweet comfort of expectation is gone. The reality that if you were born as a son to a blacksmith in the Medieval era, you could rest assured that that’s what your future had in store. Same with your son and your son’s son. They all get the same freedom. A liberation from ever being in a position to feel that their expectations were betrayed.

In the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville, the french lawyer and historian, put it this way:

Having never conceived the possibility of a social state other than the one they knew, and never expecting to become equal to their leaders, the people did not question their rights. They felt neither repugnance nor degradation in submitting to severities, which seemed to them like inevitable ills sent by God.

But of course, in America, democracy has now broke down every barrier to expectation. And this is again arranged by our visions as children — dreams of achieving as far as our imaginations would allow — unaware of the disappointment being stored up all the while.

And indeed disappointment has become pervasive in the western world, making it part of the holy trinity of Anxiety: expectation, uncertainty and disappointment.

So there you have it. So long as we live in a democracy and keep dreaming, we are unfortunately justified in our anxiety over uncertainty for our future, and whatever disappointment may come as a consequence too.

But this is no trivial thing. The climbing suicide and depression rates can attest to that. So then how can we fix this western epidemic? Are there any solutions?

Fortunately yes, and I’ll talk about that more in my next newsletter, but before I go, here’s a quick recap:

Status no longer depends on a person’s unchanging identity that was handed down to them by their parents and grandparents and so-on (unless your mother is quite literally a queen)

Instead, it hangs on the competence of a person in a fast-moving economy — their ability to perform insofar as their performing results in dollar bills.

Thus, we get status anxiety when we don’t get the dollar bill we expected to have — a result of the modern story framing poverty as an indicator of one’s inherent value being less than.

Which is also exacerbated by our peers (reference points) getting more dollar bills than us.

Leading to state of disappointment and further anxiety for the future.